For me and I’m sure many other egg lovers, there’s a certain satisfaction in cracking an egg. Eggs are always on my menu, whether I’m making a simple fried rice dish for dinner or a fluffy omelet for morning. I usually purchase them from the store, packed in those familiar boxes, but sometimes I acquire them at the farmer’s market. As time went on, I came to understand that cracking the codes on these boxes is a necessity rather than just an interest.

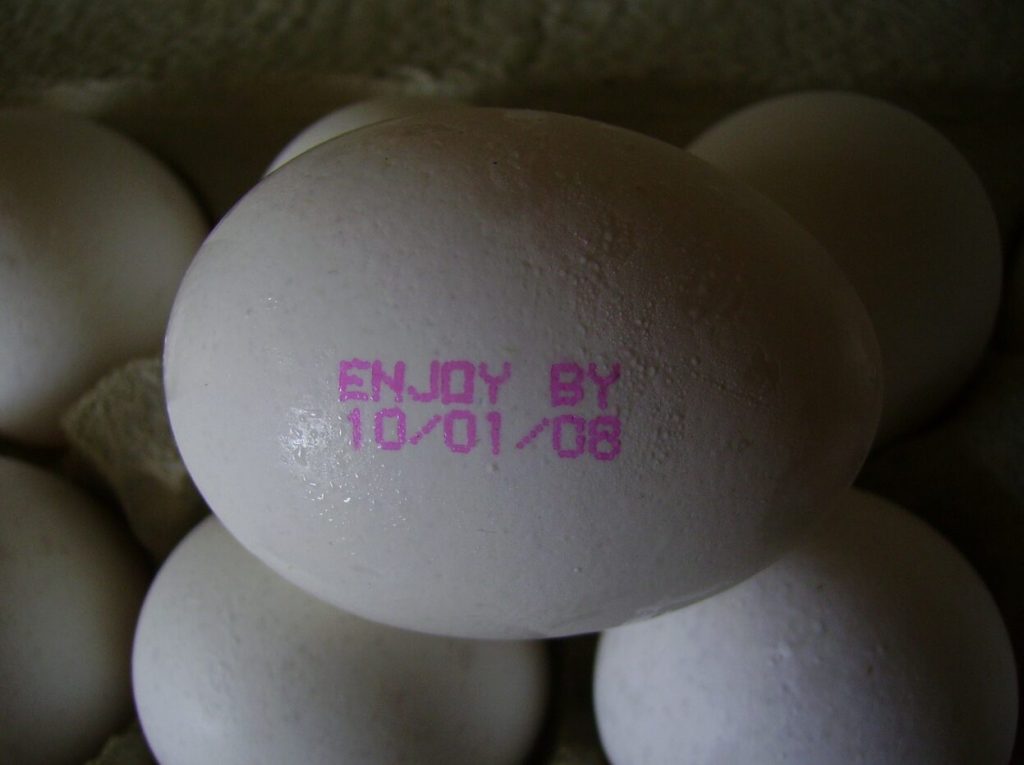

Have you ever wondered what the numbers on an egg carton meant when you looked at them? Even though those numbers appear to be some sort of code, once you know what they stand for, they are quite simple to comprehend. So, let me to clarify, shall we?The Julian Date is the birthday of your egg.First, there is the three-digit code, which appears to be made up of a random assortment of digits. The Julian date is a reference to the precise day of the year that the eggs were packaged. There are 365 days in a Julian calendar. For example, the code 001 indicates that the eggs were graded on January 1st if you observe it on the carton. A 365 code denotes December 31st. Seems very straightforward, doesn’t it?I can still clearly remember my initial experience with this. As I was examining an egg carton in my kitchen, I had the impression of Sherlock Holmes cracking a case. “Well, these eggs date back to March 15th,” I mused to myself, feeling somewhat smug. It’s similar like having the password to a select group of ardent egg enthusiasts.The Source of Your Eggs: The Packaging Plant CodeYou might see a code next to the Julian date that starts with the letter “P.” This is the plant code, and it tells you where the eggs were processed. In the event that eggs are recalled, this information is quite helpful. Knowing the plant code can help you determine whether the recall applies to your particular carton. It is a minor detail, but it makes a big difference in guaranteeing the safety of the eggs you eat.Why This Is Important. I know you’re probably wondering why any of this matters. What use does it serve to know the plant code and the Julian date? Alright, let me clarify this for you.Due to salmonella infection, there was a massive egg recall a few years ago. I had bought a few cartons from the supermarket, so I can remember it like it was yesterday. I wondered if the eggs in my refrigerator were among those being recalled, and I started to panic. But then I recalled the Julian date and the plant code. When I looked around and saw they were safe, I sighed with relief.

Eggs Lose Their Freshness and Expiration Over Time

The way the eggs are handled to ensure freshness is another crucial aspect of these standards. As long as they are stored properly, eggs can be consumed up to 30 days after the date they were packaged. This is where the Julian date comes in handy.After I come home from the supermarket, I’ve developed the habit of looking up the Julian date. It resembles a little ceremony. I take note of the date, conduct a quick arithmetic calculation, and keep track of when to use them up. It’s an easy way to make sure I always have fresh eggs, which makes a big difference in the dish’s flavor.Safety and Quality: More Than Just DatesTo ensure that you receive the tastiest eggs, there’s more to it than just knowing the Julian date and plant code. If you’re looking for anything specific, you may also search for additional markings on the carton, such the USDA grade shield and the terms “pastured” or “organic.”The fact that eggs with the USDA grade mark have undergone quality inspection and meet specific requirements is another benefit of purchasing them. The best eggs, grade AA, have solid yolks and thick whites, making them ideal for poaching or frying. Even though Grade A eggs are marginally less solid than Grade AA eggs, they are still excellent for baking and cooking.

Pastured and Organic EggsIf you enjoy eggs from hens that are allowed to roam freely, you might want to search for phrases like “pastured” or “organic.” Chickens that are fed organic feed and do not receive antibiotics are the source of organic eggs. Eggs without cages are produced by hens that are free to roam around and consume real food, which enhances the flavor of the eggs.Allow me to explain how, for me, all of this information came to be. During a Saturday morning, I made an omelet. I reached for the egg carton, saw the Julian date printed on it, and was relieved to see that the eggs had only been packed a week before. They were flawless and fresh. I broke off a few and placed them in a bowl; their rich, orange yolks suggested that they were fresh.I continued whisking the mixture after adding some milk, salt, and freshly ground pepper. I cracked the eggs into the skillet after melting a dollop of butter and allowing it to froth. After the omelet rose beautifully, I folded it and topped it with the cheese and sautéed mushrooms. Because the eggs were so fresh, I’m confident that the omelet turned out to be the greatest I’d made in a long time.

Try to decipher the codes the next time you are holding an egg carton. Knowing the Julian date and the plant code is more than just information; it is a guarantee of the quality and safety of the eggs you eat. You may improve your egg talents by knowing what those numbers represent, whether you’re scrambling eggs in the morning or baking a cake in the evening.As it turns out, it’s a fun but tiny part of the culinary experience. Who wouldn’t want to have breakfast and learn something new?

My Best Friend Asked Me to Watch Her Kids for an Hour – I Didn’t See Her Again for 7 Years

Melanie agrees to watch her best friend’s kids for an hour, but she doesn’t return. Melanie files a missing person report and takes on the role of mother. Seven years later, a seaside encounter with a familiar face shatters the family’s newfound peace, reigniting old wounds and unresolved emotions.

I’m Melanie, and I want to tell you about the most significant day in my life. I had just gotten home from a grueling day at the office.

A woman rubbing at her temples | Source: Pexels

All I wanted was to kick back with a glass of wine and lose myself in some cheesy rom-com. You know, the kind where you don’t have to think too hard, just laugh at the predictable plot and cry a little at the happy ending.

But life, as it often does, had other plans.

I was just about to hit play when there was a knock at the door. I wasn’t expecting anyone, so I hesitated, peeking through the peephole.

A woman standing by a door | Source: Midjourney

To my surprise, it was Christina, my best friend. And she wasn’t alone. She had her two kids, Dylan, who was five, and baby Mike, barely two months old, bundled up in her arms.

“Melanie, I need your help,” she said, her voice trembling. “I have to see a doctor urgently. Can you watch the boys for an hour? Just an hour, I promise.”

Chris looked desperate, and honestly, it scared me. She was always the strong one, the one who had it all together. Seeing her like that, so vulnerable, was jarring.

A woman standing on a porch with her kids | Source: Midjourney

I felt a knot form in my stomach, but I couldn’t say no to her. How could I?

“Of course, Chris,” I said, trying to sound more confident than I felt. “Come in, let’s get you sorted.”

She handed me baby Mike and kissed Dylan on the forehead.

“I’ll be back soon,” she said, her eyes wide with an urgency I’d never seen before. And then she was gone, leaving me with two kids and a head full of questions.

A woman standing in a doorway with two kids | Source: Midjourney

That hour turned into two. Then three. Night fell, and Chris still hadn’t returned.

I called her phone repeatedly, but it went straight to voicemail. The unease grew into full-blown panic. I put the boys to bed, trying to keep my worry from spilling over onto them.

Days passed with no word from Chris. I filed a missing person report, hoping the police could find her quickly. In the meantime, I was left to care for Dylan and Mike. Temporarily, I told myself. Just until Chris comes back.

A woman staring thoughtfully out a window | Source: Pexels

But she didn’t come back. Weeks turned into months, and the boys started to feel more like my own kids than Chris’s. They began calling me “Mom,” a habit that started naturally and felt strangely right.

The first time Dylan called me Mom was at his school’s parent-teacher meeting. He ran up to his friends and proudly introduced me, “This is my mom!”

My heart nearly burst. I knew then that I couldn’t just be their temporary guardian anymore.

A woman hugging a boy | Source: Midjourney

They needed stability, a real home, and someone who would be there for them always. So, I started the legal process to adopt them. It wasn’t easy, but it was worth it.

Mike’s first steps were a cause for celebration, a moment of pure joy that we shared together. Dylan’s first soccer game, where he scored a goal and ran to me shouting, “Did you see that, Mom? Did you see?”

Those moments stitched us together as a family.

Fast forward seven years, and we went to a seaside town for vacation.

Seaside town | Source: Pexels

The ocean breeze was refreshing, and the boys were laughing, carefree and happy. We walked along the shore, collecting shells and splashing in the waves. It was perfect.

Then, out of nowhere, Dylan froze. He pointed to a woman in the crowd.

“Is that her?” he asked, his voice shaking. I followed his gaze and felt my heart stop. It was Chris. Older, worn, but unmistakably Chris.

“Yes, it is,” I whispered, unable to believe my eyes.

Dylan didn’t wait.

A shocked boy on a beach | Source: Midjourney

He took off running toward her, leaving Mike and me standing in the sand, our breaths caught in our throats. My heart pounded in my chest as I watched my son sprint towards the woman who had left him so long ago.

“Why did you leave us?” Dylan shouted, his voice carrying over the sound of the waves. “Do you know what you did? We waited for you! Mom waited for you!”

The woman turned, eyes wide with shock, but then her expression hardened.

A woman on a beach | Source: Pexels

“You must have me confused with someone else,” she said, her voice flat and devoid of emotion. “I’m not who you think I am.”

Dylan stood his ground, tears streaming down his face. “LIAR! I DON’T CARE IF YOU PRETEND THAT YOU DON’T KNOW ME, OR SAY I’M CONFUSED! I KNOW THE TRUTH. YOU ARE NOT MY MOTHER, SHE IS!”

He turned then and pointed at me, his eyes burning with a fierce protectiveness that made my heart ache.

I walked over, holding Mike close.

A woman holding a boy on a beach | Source: Midjourney

“Chris, would you say something, please? We deserve to know what happened,” I said.

But she turned away, staring out at the ocean with a face like stone.

I placed my hand on Dylan’s shoulder.

“Dylan, let’s go,” I said softly, but he shook his head, not done yet.

“When I grow up,” Dylan continued, his voice breaking but strong, “I’ll make a lot of money and buy my true mom a house and a car and do anything to make her smile! Because she deserves it! And you deserve to spend your whole life alone!”

A boy shouting | Source: Midjourney

With that, he turned on his heel, leaving Chris—or whoever she claimed to be—standing there, stunned and silent.

We left the beach in silence, the weight of the encounter pressing down on us. The boys were quiet, their usual chatter replaced by the heavy silence of unresolved emotions.

There was no cheering the boys up as we headed to the hotel to check-in. It took a while, but eventually, we headed to our room.

I was relieved to get away from the beach, but the sight that greeted us wasn’t comforting.

A hotel room | Source: Pexels

The bathroom was a mess, clearly untouched by housekeeping.

“Just what we need,” I muttered under my breath. I picked up the phone and called the front desk. “Hi, we just checked into room 212, and the bathroom hasn’t been cleaned. Can you send someone up, please?”

A few minutes later, there was a knock at the door. I opened it to find a cleaning lady standing there, her head down, face hidden by a worn-out cap.

“Come in,” I said, stepping aside.

A hotel maid standing in a corridor | Source: Midjourney

She moved slowly, deliberately, and something about her seemed familiar.

When she finally looked up, I gasped. It was Chris again!

“You’ve got to be kidding me!” I yelped.

“What are you doing here?” Dylan said, his voice a mix of disbelief and anger. “Are you following us?”

Chris—or Alice, as her name tag read—looked like she was about to collapse.

“I… I work here. I came to clean the bathroom,” she said, her voice barely above a whisper. “But now… I’m sorry, Melanie. I never meant for any of this to happen.”

An emotional woman | Source: Pexels

“I was desperate when I came to you that day,” she continued as tears ran down her face. “I’d sunk into a real dark place and I just… I couldn’t hold myself together anymore, let alone take care of two kids.”

“Then you should’ve asked for help,” I snapped. “I would’ve done anything I could…”

My voice trailed off as I stared into Chris’s eyes. The truth hit me like a truck: The woman I’d always thought was so strong had been struggling in secret, unwilling or unable to reach out for help.

A woman crying | Source: Pexels

Her leaving the boys with me was the most she could do. It was her last, desperate attempt to save her children and herself. And it broke my heart.

“It never had to be this way, Chris.”

“There was no other option,” she replied, her voice heavy with regret.

Dylan’s face hardened, and he stepped in between Chris and me. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a dollar, pressing it into Chris’s hand.

“Don’t worry about the bathroom,” he said coldly. “We will clean it ourselves.”

A one dollar bill | Source: Pexels

Chris stood there, tears welling up in her eyes, as Dylan shut the door in her face. He then turned to me, and I pulled him into a tight hug.

I held my boys close, comforting them as best I could. A part of me was grateful we’d run into Chris. We finally had some closure on why she did what she did, even if Dylan and Mike were too young to understand.

“Can we go home, Mom?” Dylan asked. “I don’t want to see her again.”

A woman hugging two young brothers | Source: Midjourney

We left within the hour.

Back home, life slowly returned to normal. The encounter with Chris became a past chapter, something we had faced and left behind.

We had survived abandonment, heartache, and uncertainty, but we had come out the other side stronger and more united than ever. Our family was a testament to the power of love and resilience, and as I watched my boys play, I knew we could face anything together.

This work is inspired by real events and people, but it has been fictionalized for creative purposes. Names, characters, and details have been changed to protect privacy and enhance the narrative. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

The author and publisher make no claims to the accuracy of events or the portrayal of characters and are not liable for any misinterpretation. This story is provided “as is,” and any opinions expressed are those of the characters and do not reflect the views of the author or publisher.

Leave a Reply